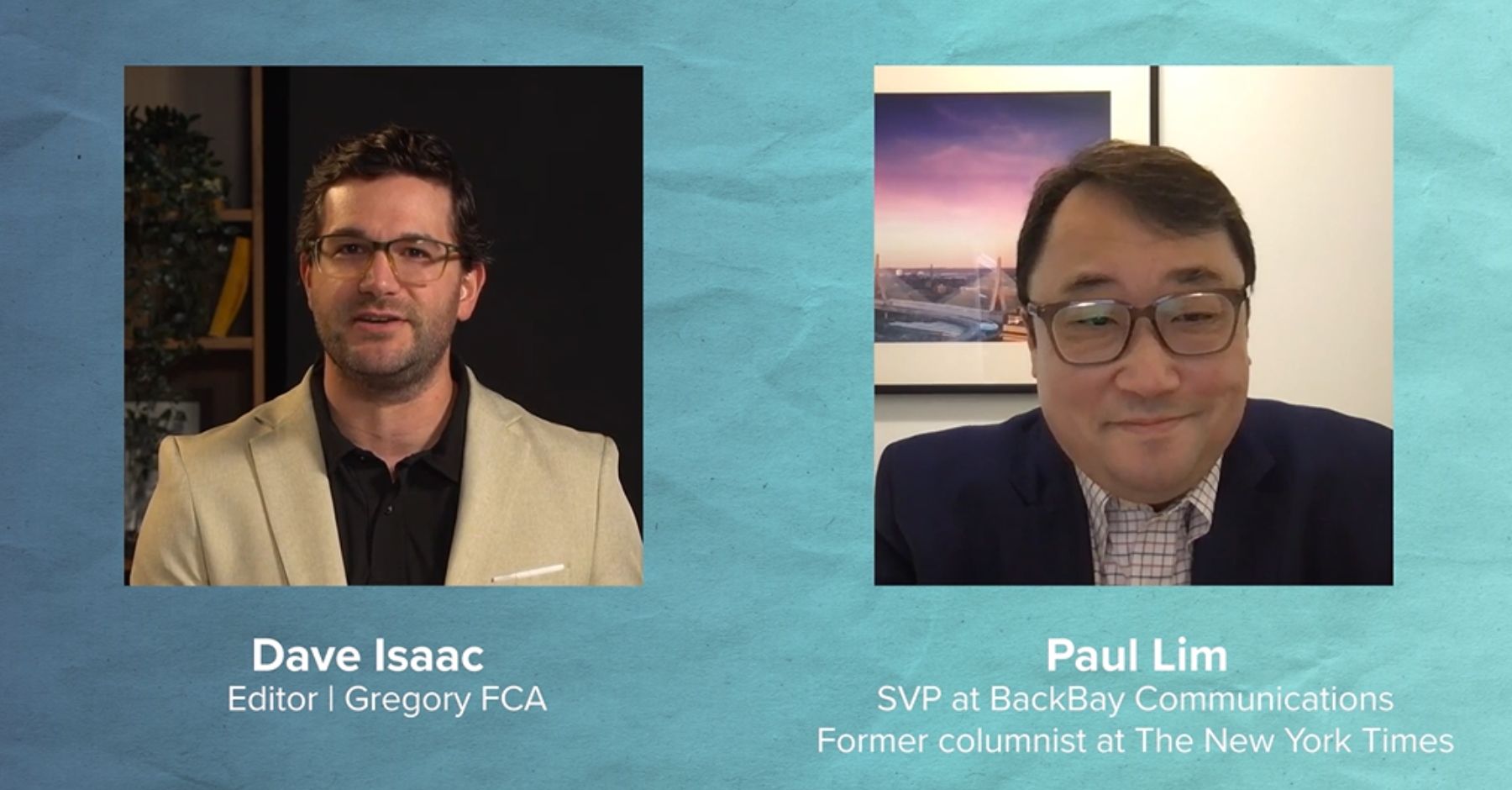

The best pitch Paul Lim ever received was two sentences long. Paul, once a reporter at top-tier publications and columnist at The New York Times, saw his share of good and bad pitches, as well as the ways financial services executives position themselves as trusty sources that journalists seek out again and again for commentary.

Now, Paul is Senior Vice President at BackBay Communications, a Gregory FCA company, focused on PR for financial services companies looking to improve their media coverage and bolster their brand on Wall Street. His experience as a reporter and insider knowledge of how stories are told gives our clients an advantage in becoming those go-to sources. That’s why we make it a point to hire former reporters — 18% of our staff used to work in the media.

Paul shares some of that knowledge in the Q&A below, including the best pitch he ever received, the two things executives need to do to increase their chances of being quoted, and one of the biggest misconceptions about working with the media.

Learn how our former journalists and experienced storytellers can help grow your business!

Watch the video:

Dave Isaac: Before we get into what life was like as a journalist, what drew you to the field? How did you get your start?

Paul Lim: I backed into journalism. I had every intention of going to Washington and working in some policy capacity. But two weeks before starting a master’s program in government administration, I was offered a two-year internship position at The Philadelphia Inquirer that allowed me to work at the paper while going to grad school at the same time. After completing my master’s, I wound up staying in journalism.

DI: You’ve worked for some renowned establishments — Money Magazine, The New York Times, U.S. World and News Report, the Los Angeles Times — what did you cover in your time as a reporter?

PL: I covered the financial markets and personal finance for most of my career. At Money, I oversaw investing and retirement planning coverage. For the Times, I wrote a Sunday investing column called ‘Fundamentally.’ At U.S. News, I was chief financial correspondent, writing about the financial markets, the economy, and corporate news. And for the L.A. Times, I covered asset managers and wrote about personal finance topics.

DI: Is there a story that you remember as being most impactful? A favorite story you got to tell? Was one particularly scary or out of your comfort zone?

PL: The biggest story I covered at Money was the global financial crisis. I’d never seen anything like it: Every morning, another giant financial institution was on the verge of utter collapse — Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, AIG, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Washington Mutual, Wachovia, RBS, Merrill Lynch. Our offices were in Rockefeller Center right across from Lehman Brothers, and as we were reporting the story in real time, we literally saw hundreds of Lehman workers streaming out of the building carrying their personal belongings in boxes and looking stunned. Throughout Midtown Manhattan, you had armed police in riot gear standing guard outside the entrances of the biggest banks and investment firms in the world. It truly felt like the world was coming to an end.

DI: What was your relationship with PR like at the time? Were you pitched stories often, and how did those communications go?

PL: I was pitched quite frequently, but it was hit or miss. The ones who got it knew there were different types of “investment” writers — those who write about market moves; those who cover the market from a top-down perspective by focusing on asset classes and allocation strategies; those who write about the market from the bottom-up by focusing on individual stocks; those who cover asset managers as opposed to market moves; and those who write about investing through a personal finance lens. The ones who got it knew what type of writer I was and pitched accordingly.

DI: What is the best pitch you ever received as a reporter?

PL: In general, I firmly believe that the best pitches are the ones that don’t just offer a thought leader — they offer the actual thought. They show the exact point of view that the expert can bring to the conversation, if not direct quotes in bullet points. But the very best pitch I ever received said simply, “Paul, so and so is in town. Want to grab coffee?” After receiving hundreds of pitches that are extremely detailed — including many that are way too long — sometimes it’s refreshing to see a one-sentence note. It’s standing out through counter programming. However, only a PR person who has put in the work over months and years to build a long-term relationship with a reporter can get away with that.

DI: What led you to PR? Was it difficult to leave the industry?

PL: My last job in journalism was as deputy managing editor at Money. I had been living in Boston at the time and was shuttling back and forth to NYC, so my situation was a bit different. When I joined Money, we were part of a large publicly traded media conglomerate, Time Warner. But print magazines weren’t growing fast enough to keep up with the rest of the company, so Time Warner spun off Time Inc. as a stand-alone, public company. Then Meredith Corp. purchased Time Inc. and told the teams at Time, Sports Illustrated, Fortune, and Money that they were looking to unload those titles. That’s when I realized that unless I was willing to move my family from Boston to NYC, I probably should think about changing careers.

DI: What surprised you the most being on this side of the communications equation?

PL: It was emotionally difficult to leave journalism, and it was awkward to start pitching former colleagues. But starting in PR was not functionally that different. It was about understanding what stories are being worked on and how a particular expert might help tell that story.

DI: Do you see the news differently now that you’re in PR?

PL: Not really. When I was a reporter, my job was to think about what the story should focus on, and then find experts to populate each segment of that story. In PR, my job is still to think about what the stories will be, and then to figure out what segments of that story my clients can serve.

DI: Our job is to get results for clients, but having contacts in the media doesn’t guarantee coverage. As a former reporter, what skills are most valuable to clients?

PL: Honestly, showing up is 80% of it. Reporters are constantly on deadline, and they’re taught not to let perfect be the enemy of the good. In most cases the perfect source can’t be reached on deadline, so they’re willing to quote experts who may not have been their first choice but who will call them back in time to meet their deadline. As a reporter, the people I quoted most frequently were CIOs or portfolio managers who were willing to speak to me in a cab on their way home or while they’re waiting for a flight at the airport. And after those early engagements, I’d go back to those experts because they could be counted on in a pinch.

DI: What kind of information would a client in financial services have that would benefit a reporter and potentially lead to coverage?

PL: A distinct point of view. Some clients think they need to offer responses that cover a broad spectrum of information and opinions. But when an expert offers an “on the one hand and on the other hand” response, there’s a sense that they don’t have strong viewpoints. Those are the people whose quotes are often the first on the cutting room floor. Similarly, some clients may choose not to argue against the premise of the reporter’s story, even if they disagree with it. But if you’re the only source who pushes back, there’s a better chance of getting into the story because 1) you have a strong point of view, and 2) the reporter needs to have someone quoted high up in the story taking the opposite position for balance. That’s the “to be sure” section.

DI: What is one thing you wish companies in the FinServ space understood about the media?

PL: There’s a misconception that reporters know exactly what they want to write about and who they want to interview. In most cases, stories are thought up at the last minute and reporters don’t know precisely the types of viewpoints they are looking for until they start reporting the story. I say this because some clients don’t want to participate in an interview unless they know precisely what questions they’re going to be asked. I can understand that. But often, reporters don’t know what questions they’re going to ask until they actually get on the phone with you and start the conversation. While it’s safer to know what questions are coming, not knowing sometimes allows you to go to the reporter and tell them what question they should be asking — and provide the answers. That can be an effective way to get your point and point of view across and build a relationship with the reporter.